Scalable AI for Science

Why AI Scientists Need High Bias and High Variance

AI for Science — and even “AI Scientists” — have become popular topics recently. AI models are starting to contribute to research in diverse fields, from biology to mathematics to machine learning. It is not hard to imagine a self-accelerating cycle: the large-scale parallel deployment of AI researchers studying and improving AI research progress, leading to a virtuous loop that some might call the singularity. Therefore, it is not hard to understand the popularity behind AI for Science.

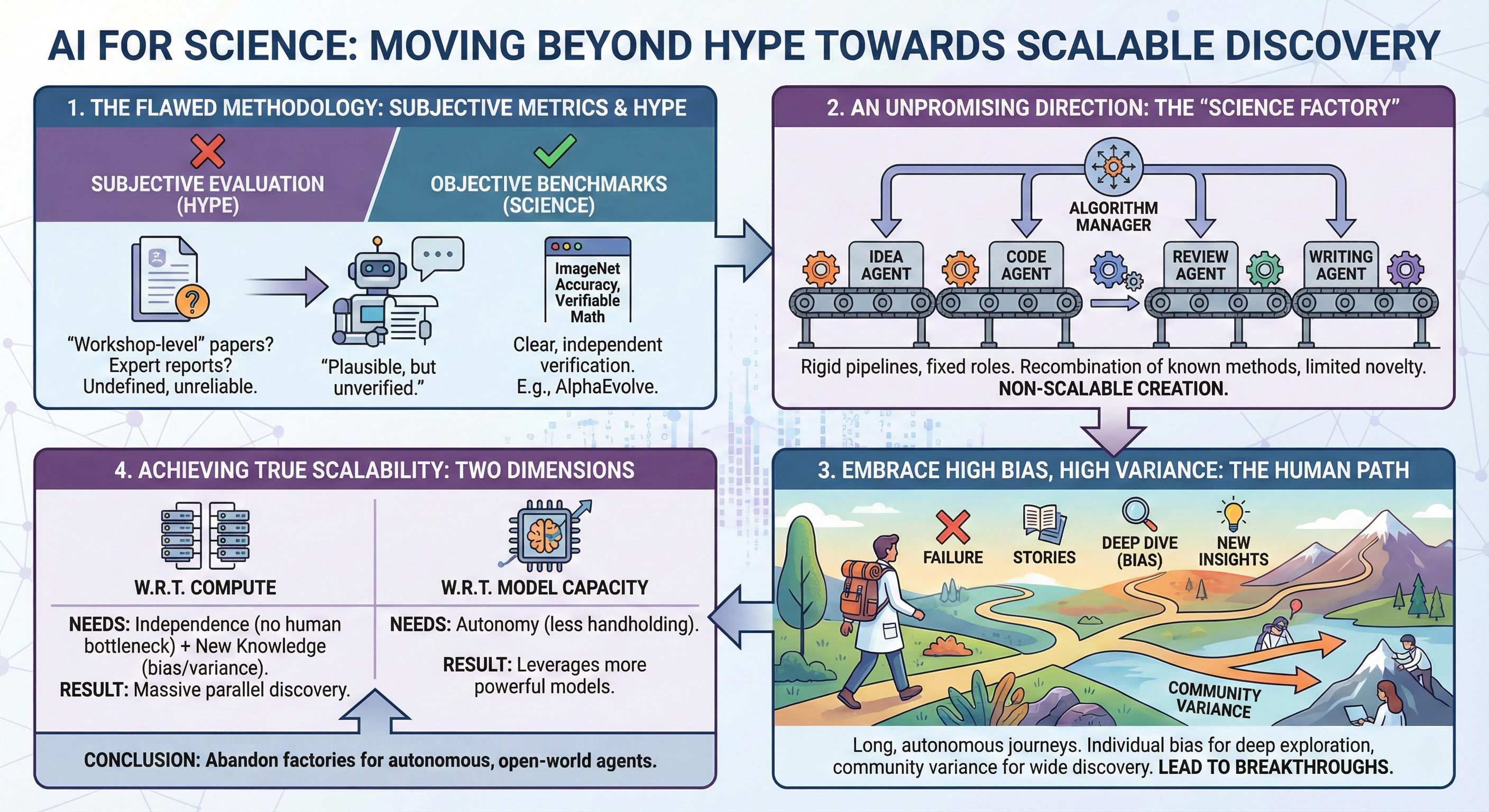

Flawed Methodology

However, popularity without deliverables remains mere hype. This is indeed true for much AI-for-Science work that lacks objective evaluation. Claims often center on the ability to generate “workshop-level” or “conference-level” papers. But this is subjective — what is the precise definition of a workshop or conference-level paper? Given the stochastic nature of the review process, it is likely that even a paper containing false claims or hallucinations could get accepted with enough luck. Moreover, LLMs — trained to predict the next word — can easily produce documents that appear plausible but lack factual support, easily misleading humans. As such, these AI-generated documents require rigorous verification by humans.

There are also works that use other subjective metrics, such as expert-evaluated accuracy per statement or reports from collaborators. The trustworthiness of these metrics depends on many uncontrollable factors, such as the independence of the expert and the definition of “accurate.”

In any case, it is unknown how scalable these approaches are. Say 1% of the generated papers contain novel methods, or 1% of the sentences generate novel insights. The effort required to filter out these papers or insights would likely consume more time than a human expert working on a research project alone, defeating the whole purpose of AI for Science. One cannot simply upscale these approaches — for example, by deploying thousands of runs simultaneously — because each output requires rigorous verification by experts. It is, at best, similar to a researcher hiring a team of untrustworthy research interns who may occasionally produce good work. The researcher will easily be overwhelmed when the size of the team grows large.

To advance in AI for Science, we must be scientific ourselves. Work in this field should always start with objective metrics that do not require subjective interpretation. Benchmarks exist for this purpose. Either one achieves higher accuracy on ImageNet classification or one does not — no expert is needed to evaluate it. A good example is Google’s AlphaEvolve

An Unpromising Direction

Besides flawed methodology, mainstream work in AI for Science is heading in an unpromising direction: the “Science Factory” mode. In essence, this involves AI agents being assigned different roles, with a centralized manager controlled by an algorithm to distribute prompts. The flow is always rigid; a typical setup has an idea agent generating concepts, a code executor/improver agent allocated to improve baselines, a literature review agent, a paper writing agent, and so on — all controlled by a central algorithm. This Science Factory mode, which also underlies AlphaEvolve, can indeed generate some strong results (such as advancing the kissing number lower bound or finding better ways of matrix multiplication), but close scrutiny reveals the direction is, again, non-scalable.

Why? If one reads the works produced by the Science Factory mode closely, the discovered methods are usually brute-force recombinations or minor tweaks of known methods. Take the program AlphaEvolve discovered for finding better matrix multiplication: it uses four different heuristics to inject stochasticity into a typical gradient descent algorithm. These heuristics are all known, but the specific combination of them, along with the large computational cost for each evaluation, enabled the discovery of the global optimum. The Science Factory mode can generate intricate recombinations of in-domain methods, but it struggles to borrow out-of-domain methods or create novel methods due to the vast search space, which renders brute-force search impossible.

Of course, there are many problems where we can push the known boundary through the intricate recombination of known methods — especially because human scientists are typically not interested in simply recombining existing works. But this is ultimately non-scalable, as one will soon find diminishing returns; endless recombination has its limits.

To create new knowledge, one must abandon the Science Factory mode and take lessons from how human scientists create knowledge. A scientist does not work in a factory. A scientist undergoes a long journey of discovery, often filled with failure and stories. These failures and stories are necessary because they lead to a high-bias, high-variance path.

Embrace High Bias, High Variance

The long journey of scientists often leads to a bias toward a particular direction or field, depending on the insights or intuition developed along the way. A machine learning researcher who likes neuroscience may often try to borrow ideas from the brain when designing an algorithm, while another who likes mathematics may focus on ensuring nice theoretical properties. These are different subjective biases, and it is hard to tell a priori which may lead to better results. But these biases can lead to deep exploration — a researcher may spend years on a research direction before it yields fruit. One example is Reinforcement Learning, where the early founders believed it was more biologically plausible than other forms of learning. It took more than three decades of their work before it was used effectively in practice.

In contrast, a researcher without bias may quickly pivot or abandon a direction when results are not immediately promising. This may indeed be more optimal if one only looks at the individual level, but not at the community level. If all researchers were “unbiased” in this way, there would not be any deep exploration leading to groundbreaking work.

These biases, coupled with the high variance of each researcher’s path due to their rich experience, make our current scientific ecosystem extremely effective in advancing discovery. High bias enables deep exploration within an individual; high variance enables wide exploration across individuals. The beauty of scientific discovery is that we do not care about the average — we care only about the maximum. We build on top of the calculus from Newton and the relativity from Einstein, not the math or physics understanding of the average citizen.

Therefore, one must abandon the traditional mindset that unbiased, minimal variance is good. Both bias and variance are good in AI-for-Science methods. The current Science Factory regime is an unbiased method — every agent has a generic role and instruction assigned, without any persistent bias that enables the long-term discovery of a direction. We should design agents to be biased and have a high-variance path. This can be made possible by letting agents develop their own paths — by giving them a high degree of autonomy in a dynamic world. The long accumulation of context, along with interaction with a dynamic world, is sufficient to ensure a high-bias and high-variance research journey.

Scalability

We often talk about scalability, but one must be prudent and ask: scalable with respect to what? In AI-for-Science, when we talk about scalability, there should be two main dimensions.

First is scientific discovery w.r.t. compute. Can we scale scientific discovery with the computational budget? Most work nowadays lacks this. As long as human collaboration or verification is needed, human effort will become the bottleneck. So for this dimension, independence is necessary, meaning the method must produce verifiable output without human help. However, even without human help, a method can still be non-scalable. For example, in the Science Factory method, one may be able to generate new ideas from the recombination of existing ones, but this is ultimately limited regardless of how many compute hours we invest, as there is no new knowledge creation. To be scalable w.r.t. compute, the method must be: (1) independent (no human guidance/verification needed), and (2) biased with high variance to lead to the creation of new knowledge. Combined, we can invest compute to run massive-scale instances in parallel — the high variance ensures a few instances generate groundbreaking results while the independence ensures easy filtration of these results without human verification.

The second dimension is model capacity. Can scientific discovery scale w.r.t. model capacity? When a new AI model is released, will the method improve? Imagine forcing Einstein to work as a code improver in a Science Factory — his intelligence would be essentially wasted. Autonomy is needed to be scalable w.r.t. model capacity; as models become more powerful, less handholding is needed. A method that relies on handholding and rigid pipelines is doomed to be non-scalable in this regard.

Conclusion

AI for Science holds great promise for our civilization, but it will easily lead to hype and a bubble with the wrong methodology and directions. We must be scientific ourselves when designing AI-for-Science methods. We should abandon the traditional mindset of handcrafting pipelines for agents and instead embrace autonomy and emergent behavior, as science flourishes in an open-world environment with diverse stories, not a factory. Only with the correct methodology and direction can one realize the goal of scalable AI for Science.