The Planning Trinity

Why General Intelligence Needs Intuition, Reason, and a World Model

What is planning? How do we learn to plan? Why do we plan? The nature of planning is fundamental in understanding intelligence and, consequently, in building artificial general intelligence. With the recent surge of large language models, there is an illusion that artificial general intelligence could be achieved by predicting the next tokens given enough data and a large enough model. Still, even with the vast amount of data used to train these large language models, they often fail to complete simple planning tasks, such as multiplication, without further fine-tuning or additional tools. This hints at a fundamental limitation of these large language models, as I argue that the ability to plan cannot be simply acquired by scaling laws, and planning is one of the most critical missing puzzles in approaching artificial general intelligence.

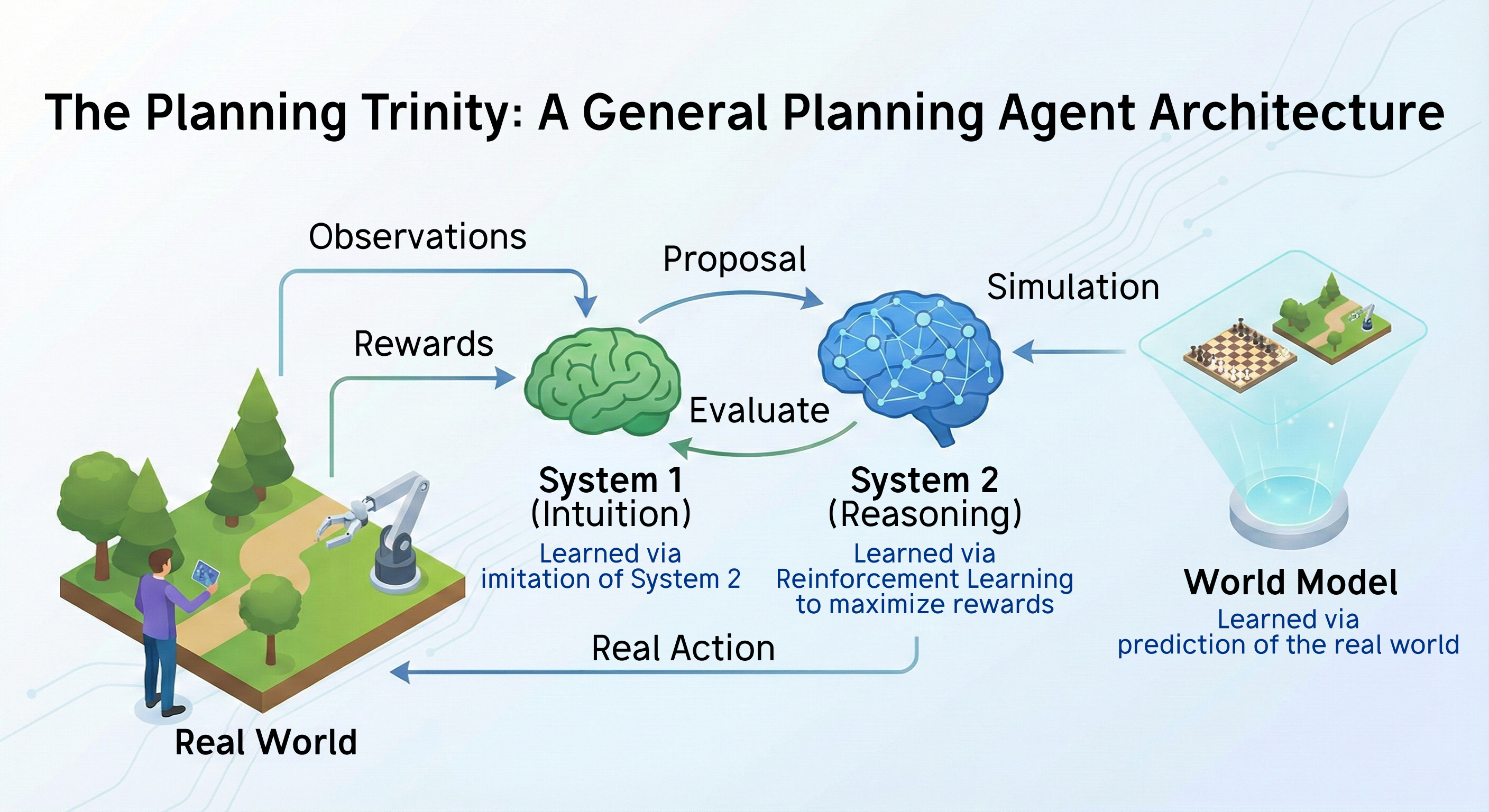

Nature has already built a general intelligent system that does not require thousands of GPUs and terabytes of data, and we need only look upon ourselves to find the key to planning. According to the dual process theory, our intelligence is equipped with two systems — System 1 and System 2. System 1 represents our instincts and allows us to act quickly without much deliberation. For example, when you see a fire breaking out, your instinct is to run. This involves System 1 as there is no need to think deliberately to arrive at this action. On the other hand, System 2 represents our deliberate thought and allows us to fine-tune our System 1. For example, in the earlier example, if you are a firefighter, then you know that you need not run and fear fire as you are well-equipped.

Why do we need two systems instead of a single system? Perhaps a simple answer is that System 1 allows us to act fast, which is often required in emergencies, while System 2 enables us to act better when there is a luxury of time. However, I argue that it is much more than that. The dual system completes the loop of policy iteration, and it is this policy iteration that leads to a virtuous loop of learning and our superior intelligence.

Consider that you have just finished reading a math textbook and start working on some exercises. At first, your instinct, or System 1, provides poor guidance as you are not familiar with the new subject. So, you use your System 2 to think carefully, possibly recalling the knowledge you have read and trying different methods until the question is solved. The virtuous loop begins — System 1 tries to imitate the output of System 2, meaning that the solution you attempted is distilled into your System 1, becoming part of your intuition. System 2 can then act by refining this improved intuition, giving even better results that are further distilled into System 1. In short, System 2 improves System 1, while System 1 imitates System 2. This forms a virtuous loop called policy iteration.

This policy iteration alone, when applied in artificial intelligence, can already lead to spectacular planning abilities. We only have to look at AlphaZero

AlphaZero completes this loop by a simple change — representing the System 1 policy with a deep neural network and training it by imitating the System 2 policy. This seemingly small change, aside from other technical details, is the core step from mediocre performance to superhuman performance in chess games. The policy iteration loop allows the system to continuously improve upon itself, leading to a virtuous cycle.

We now know how System 1 learns — by imitating System 2 (it is reasonable to believe that in animals, System 1 is also shaped by genetics; both nature and nurture contribute to it). But what about System 2? How does our System 2 learn? I would argue that it is largely based on reinforcement learning — if we receive rewards after some actions, then we repeat doing the same action, and if we receive a penalty, then we avoid doing the same action. This kind of learning is called instrumental conditioning and is widely observed in animals. I would further argue that this is the current missing key to a fully general planning agent.

In the current state-of-the-art planning algorithms that involve these two systems, such as AlphaZero, the System 2 policy is fixed and not learned. For example, in AlphaZero, the System 2 policy takes in the System 1 policy and uses a handcrafted algorithm, namely MCTS, to output an improved policy. The System 2 policy is not represented by any neural networks, and there is no need for learning this policy. If we take this analog to our intelligence, it means that our consciousness is nothing but a fixed algorithm acting on our instinct. Apparently, most of us won’t agree with this statement. Research on how animals plan also shows that they do not employ any rigid planning algorithms such as MCTS. We plan flexibly and efficiently — we do not plan how to brush our teeth, we do not make useless plans such as walking one step forward then one step backward; but if we only follow a fixed planning algorithm, we need to plan for all these things.

One may argue that algorithms such as AlphaZero already achieve superhuman performance in chess games, so there may not be merit in learning this System 2 besides computational cost. And with the advance of technology, computational cost is not a concern. Why should we be interested in learning this System 2 at all? We should dedicate our efforts to improving these handcrafted planning algorithms instead, as is the current focus of the research community.

To answer the question, let us discuss the third component of planning that is often overlooked — the world model. The world model represents our knowledge of how the world evolves and is necessary for planning. For example, in the earlier firefighter example, you know that you are well-equipped, and you foresee that your equipment would protect you from fire. This is part of your world model. Without this knowledge, your System 2 cannot improve upon System 1 — as System 2 operates by combining your knowledge about the world with your instincts. In chess games, the world model is simply the knowledge of how each chess piece moves. We can simulate the chess game and search for the best move exhaustively, assuming we have infinite computational power. MCTS could be viewed as a much more efficient way of searching that is guided by System 1 output. Nonetheless, there is a core assumption underlying all this — we have a perfect world model and so we can simulate the world perfectly. But in reality, this assumption breaks unless you have a supercomputer that can simulate every atom in the world.

This perfect world model assumption underlies most, if not all, handcrafted planning algorithms ranging from MCTS, breadth-first search (BFS), depth-first search (DFS), etc. This perfect world model assumption need not hold exactly for handcrafted planning algorithms, as is shown in MuZero

Another constraint of handcrafted planning algorithms is the inability to handle abstract world models. If you are planning about which restaurant to go to tonight, will you think about every single step from exiting your home to arriving at that restaurant? Possibly not. We can plan abstractly — in terms of states, actions, and time. We have abstract knowledge that need not be expressed by a particular state — we know one plus one is two and do not need to think about two apples concretely. These kinds of abstract world models are likely not able to be handled by any handcrafted planning algorithm.

Nonetheless, the ability to plan in environments without a perfect world model, and the ability to plan abstractly, are necessary for artificial general intelligence. I argue that these two abilities can only be acquired by a learned System 2, represented by a deep neural network. This is one of the core motivations of the Thinker algorithm

Unfortunately, there have been many attempts that miss one of these three components or mesh the components together. For example, in early learning to plan works, researchers often attempt to merge System 1 and System 2 into a single system, and train it by either supervised learning or reinforcement learning. The lack of a separate System 1 makes these methods not work in complex environments — without good instincts, the agent fails to learn how to search for a good plan and evaluate a plan in complex environments. This lack of System 1 and System 2 separation arguably leads to the scarce number of research in learning to plan, as it is tempting to conclude from these early results that learning to plan is too difficult for an agent and so we should focus on handcrafting how to plan. Asking an agent to learn to plan without providing instincts is similar to asking a person to drive a plane without providing guidance — it does not work as the task is too difficult. But if proper instincts or guidance is provided, then the agent can learn to plan as shown in the Thinker algorithm.

Another mistake is to mesh the world model and System 1 together and call it the world model. As both the world model and System 1 are outputs to System 2, it may be tempting to mesh both components into a large neural network and simply call it a world model. But the world model and System 1 are distinct in nature — the former represents our knowledge about the world while the latter represents our intuition on how to act. Even though it is seemingly a terminology issue only, it often leads to problems in extending a general planning system. For example, System 1 can be trained by pure imaginative experience from the world model, but it does not make sense to train the world model by imaginative experience as it is the output of the world model itself. This may explain why so far there is no extension of AlphaZero-like algorithms to use imaginative experience (instead of off-policy real experience) to train System 1.

In conclusion, I propose that a general planning agent requires three essential learned components, which I call the Planning Trinity: a world model capturing environmental dynamics, a fast and intuitive System 1 policy proposing actions, and a slower, deliberative System 2 planning process refining those proposals through extensive reasoning. These components should be learned separately to optimize their distinct roles but must also interface seamlessly to enable a virtuous cycle of learning and improvement.

The history of machine learning provides compelling evidence for the power of learned approaches over handcrafted ones. Techniques like deep learning have consistently outperformed engineered feature representations and heuristics across a wide range of domains. However, this history also suggests that it often takes significant time and effort for the research community to recognize the limitations of our current handcrafted approaches and fully embrace learned alternatives.