The Thinker Task

Decomposing reasoning into Fast and Slow Thinking to train LLM's System 1 & System 2

Dual Process Theory and The Thinker Task

Most Large Language Models (LLMs) nowadays are enhanced for reasoning through Reinforcement Learning (RL) on Chain-of-Thought (CoT) data. Despite the effectiveness of methods like those used in DeepSeek-R1

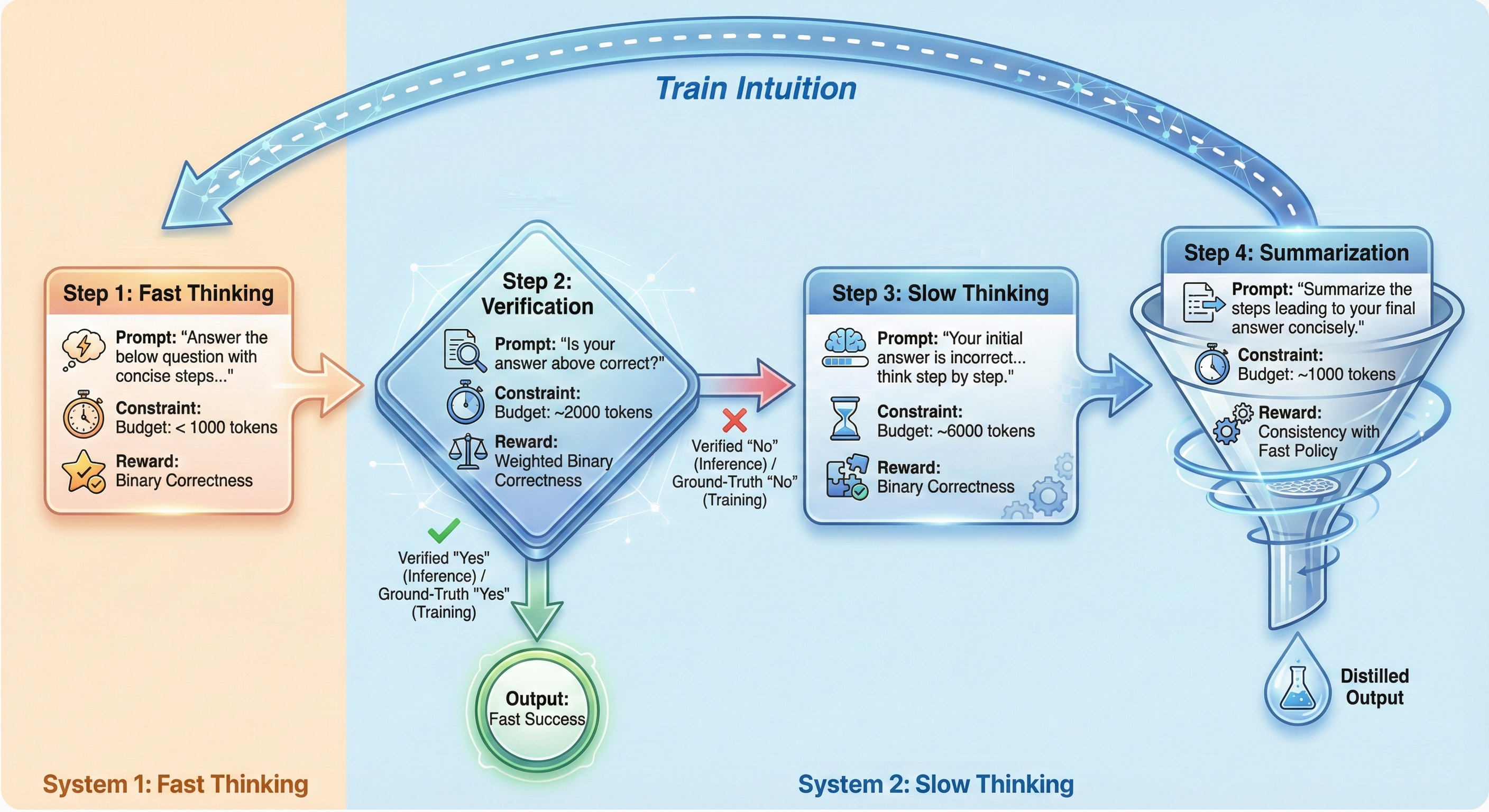

The answer is yes. An alternative way of training a reasoning model involves decomposing the Question-Answering (QA) task into distinct stages, where different “modes” of thinking are trained with specific rewards. We refer to this method as the Thinker Task. This idea proposes a structured environment to explicitly train intuition, verification, and refinement capabilities.

Inefficient Temporal Credit Assignment

Let’s examine why current reasoning models are inefficient. Consider a standard RL setting for reasoning, such as the GRPO algorithm used to train DeepSeek-R1

This leads to a problem of inefficient temporal credit assignment. Because the reward is a scalar applied to the whole sequence, the model cannot distinguish which steps were crucial reasoning and which were futile backtracking or anxious rambling. As a result, the model learns that “long context” correlates with reward, often leading to “overthinking” where the model doubts correct answers or verifies simple facts unnecessarily. Consequently, intuition—the ability to identify promising paths rapidly—is not explicitly trained.

The Solution: The Thinker Task

To address this, we propose decomposing the monolithic QA task into a four-step process, allowing for precise reward signals at each stage. This structure forces the model to develop distinct capabilities for intuition and deliberation.

As illustrated in the figure above, the Thinker task unfolds as follows:

- Fast Thinking (System 1): The agent must answer concisely within a strict token budget (e.g., 1000 tokens). This forces the model to rely on intuition rather than extensive search.

- Verification: The agent evaluates its own fast answer. It outputs a binary “Yes” or “No” regarding correctness.

- Slow Thinking (System 2): Triggered only if the verification is “No” (or if the fast answer is actually wrong during training). The agent is given a generous token budget (e.g., 6000 tokens) to refine the answer and correct mistakes.

- Summarization: If the Slow Thinking answer is correct, the agent must condense that long reasoning path into a concise summary.

Training with Local Rewards

The key to the Thinker task is that we do not use a single global reward. Instead, we apply specific rewards to each step, facilitating precise credit assignment.

Fast Thinking Reward: The reward for the first stage is strictly binary based on the correctness of the initial rapid answer \(y_{fast}\):

$$R_{fast} = \mathbb{1}\{y_{fast} = y^*\}$$

This explicitly trains the model’s intuition to find the correct answer without relying on long computation.

Verification Reward: The verification step is critical. If we simply rewarded accuracy, the model might learn to always say “No” if its fast accuracy is low. To prevent this mode collapse, we use a weighted reward based on the trailing accuracy of the fast step, denoted as \(p_{fast-acc}\):

$$ R_{verify} = \begin{cases} (1 - p_{fast\text{-}acc}) \cdot \mathbb{1}\{y_{verify} = \text{Yes}\} & \text{if } y_{fast} = y^* \\ p_{fast\text{-}acc} \cdot \mathbb{1}\{y_{verify} = \text{No}\} & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} $$

This ensures the agent is incentivized to evaluate the specific instance rather than relying on prior probabilities of success.

Slow Thinking Reward:

If the initial answer is flawed, the model enters the Slow Thinking stage with a larger token budget. The goal here is to fix the errors identified during verification. The reward is a straightforward binary correctness signal:

\[R_{slow} = \mathbb{1}\{y_{slow} = y^*\}\]This task preserves the opportunity for the agent to learn general complex search strategies, but restricts it to cases where intuition has already failed.

Summarization Reward: The final step closes the loop. We want the model to distill the “Slow Thinking” success into a form that “Fast Thinking” can learn from. The reward here combines correctness with a consistency term:

$$R_{summary} = \mathbb{1}\{y_{summary} = y_{slow}\} + c \log P(a_{summary} \mid x_{fast})$$

Here, we reward the model for generating a summary that is not only correct but also has high likelihood under the Fast Thinking prompt \(x_{fast}\). This encourages the model to form a strong association between the original question and the concise solution path.

Experimental Results

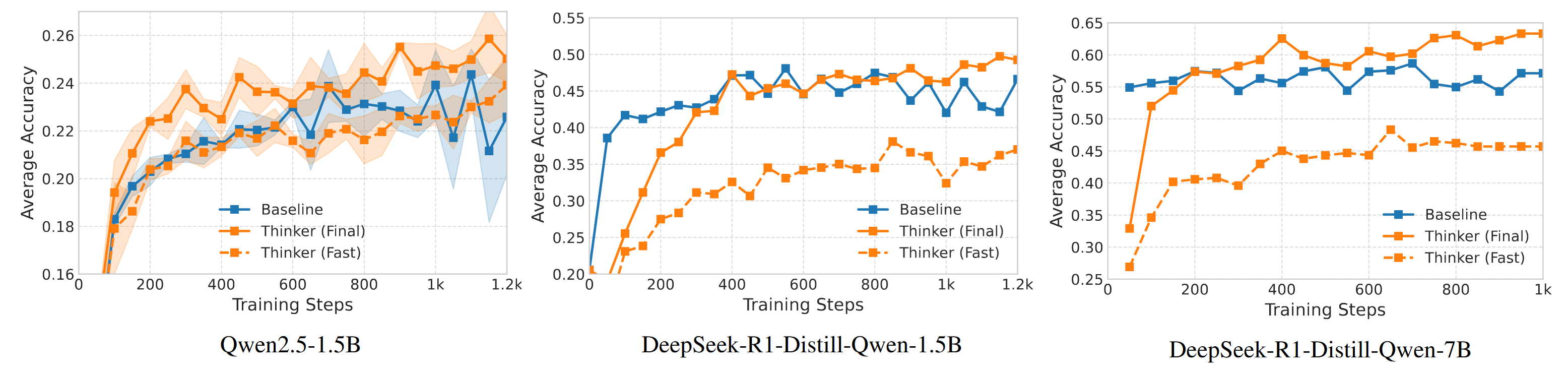

Does separating these cognitive processes actually work? We fine-tuned three models—Qwen2.5-1.5B, DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Qwen-1.5B, and DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Qwen-7B—using the Thinker task and compared them to baselines trained with standard QA RL.

The results in Figure 2 demonstrate a virtuous loop across all model sizes. We observe that the Thinker agent’s Fast Accuracy (dashed orange line) steadily improves alongside its Final Accuracy (solid orange line).

This approach yields significant performance gains: the structured Thinker task consistently outperforms the standard vanilla QA task across models. For the R1.5B model, the full Thinker task improved average accuracy across math benchmarks from 45.9% to 51.0%. Crucially, this structure allows for much more efficient token usage during inference; for instance, on the MATH500 benchmark, the “Fast Thinking” mode achieves 80.9% accuracy using only 600 tokens, whereas the baseline requires 2780 tokens to achieve 86.2%.

Qualitative analysis reveals that while the Fast Thinking mode learns to rely on quick heuristics—which may sometimes be inaccurate—the Slow Thinking mode successfully compensates by learning to perform a careful, deliberate search to correct those initial errors.

Conclusion

The Thinker task represents a shift from treating reasoning as a black-box sequence generation to viewing it as a structured cognitive process. By enforcing a separation between intuition (Fast Thinking) and deliberation (Slow Thinking), we not only achieve higher accuracy but also significant inference efficiency. The Fast Thinking mode can be deployed as a standalone “light” model for simpler queries, while the full system remains available for complex problems. This mirrors the efficiency of biological cognition: we do not engage deep deliberation for every task, and perhaps our AI agents shouldn’t either.

If you are interested, visit our open source repo here or read the full paper here.